How Indian Media Fabricated a Story of 'Rape and Murder' in Bangladesh

On December 13, 2024, several Indian news outlets reported that two elderly Bangladeshi women had been detained after illegally crossing the border into India. The women, identified as Ado Barman and Kanju Bala, both Hindus, were taken into custody by the Border Security Force (BSF).

The arrests prompted a wave of stories in Kolkata-based media outlets, speculating about the reasons behind their crossing. The Sangbad Pratidin, ABP Ananda, TV9, Hindustan Samachar, ETV Bharat, among other outlets, suggested that the women were fleeing religious persecution in Bangladesh.

Sangbad Pratidin ran a sensational headline: “Daughter torn apart — Bangladeshi granny recounts bone-chilling persecution of Hindus after fleeing across the border.”

Beneath the headline, the online edition added an insert: “She would rather remain detained here than returning to home.”

The story centered on 87-year-old Kanju Bala, whom the paper claimed had endured unspeakable violence after the ouster of Sheikh Hasina’s pro-India government on August 5, 2024, when mass student-led protests forced her from power.

5 Victims of Murder, Rape and Disappearance from One Family!

The report of Sangbad Pratidin, by journalist Shankarkumar Roy, opened with lurid detail:

“Her daughter was dragged from the house, subjected to brutal assault, and murdered by fundamentalists. When her body was found, no one dared to perform the funeral. Fear of death haunted every moment. Eventually she was forced to flee, only to be captured by the BSF after crossing the barbed wire. Through tears she described the horrors of Padma’s far shore.”

According to the account, Bala had eight children. Of them, five had fallen victim to post–August 5 violence: one daughter raped and killed, two daughters dead from hunger, a son abducted, and another rendered mentally unstable and left to wander Dhaka’s streets.

Other outlets — ABP Ananda, TV9, Hindustan Samachar, Shirshotimes, and ETV Bharat — carried similar descriptions of the story.

While Sangbad Pratidin’s website did not name her, its December 13 e-paper referred to her as “Kanju bala.” ETV Bharat also broadcast a video interview, identifying her as “Kanju Bala”.

Bellow is part of the conversation Kanju Bala had with a journalist as shown in that video interview:

Reporter: Why did you enter India?

Bala: I’m coming to my daughter’s house.

Reporter: Were you beaten in Bangladesh?

Bala: Yes, persecuted.

Reporter: Did you cross the fence?

Bala: Yes.

Reporter: What’s the situation there?

Bala: They beat us, broke our houses. We have no place to live. They cannot stand Hindus.

After Sheikh Hasina fled to India on August 5, one of the recurring narratives amplified by sections of the Indian press and on social media was that a “genocide of Hindus” was unfolding in Bangladesh. The story built around Kanju Bala fit squarely into that narrative.

The Dissent investigated Bala’s claims as reported in Indian media.

However, it’s important to note that several international human rights organizations expressed concern over the safety of minority communities in the aftermath of the uprising and called for thorough investigations into reported incidents.

At the same time, however, international media outlets and fact-checking groups noted in multiple reports that sections of India’s mainstream press had exaggerated the situation — and in many cases circulated false or misleading information about the plight of Bangladesh’s minorities.

Incorrect Address

Indian reports gave her address as “Jothai Sudpur village, Gajipur police station, Dinajpur district.” But Dinajpur has no such police station, and no village by that name.

In the ETV Bharat video, when asked about her home, Bala mentioned: “Jashai Hat, Shuddhpur (or Shukdebpur).”

Following this lead, The Dissent found a place named “Jashai Hat” in Parbatipur, Dinajpur. There is also a nearby village called ‘Paschim Shukdebpur’. Kanju Bala’s family live there.

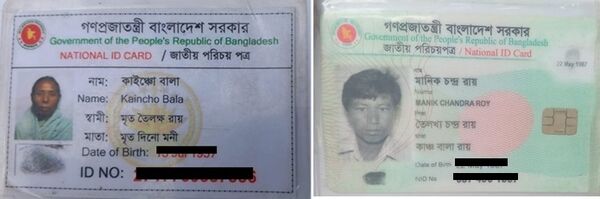

Her National ID card spells her name as Kaincho Bala, born on July 13, 1937.

The Family Speaks

In April 2025, The Dissent identified Bala’s relatives. In June, a team of journalists visited Kaincho’s son’s household in Paschim Shukdebpur.

Her eldest son, Rabidash Roy, had been missing since around the year 2000 following a domestic quarrel, according to his wife Arti Bala and their sons, Nitai and Arjun– Kanicho Bala’s two grandsons.

Kaincho’s younger son, Manik Chandra Roy, lived nearby in Chirirbandar’s Amalpur village (in Dinajpur), where he worked in brick kilns. The Dissent interviewed him as well.

Of Bala’s three daughters, the eldest, Baneshwari Roy, had died of natural causes years earlier. Another, Shefali Roy, had been married in India long ago and remained there. The youngest, Dolly Rani Roy, physically disabled, had died around 2006–07.

In short: Bala had five children, not eight. Of them, one missing, two deceased long before 2024, one long settled in India, and one alive and well in Dinajpur.

“There was no attack on my house, ever,” said Manik Chandra Roy, Bala’s only child currently living in Bangladesh.

“I don’t know when or why my mother went to India. She never told me she was going there. Maybe she went to visit my sister in India.”

Family members and villagers uniformly denied any communal violence in their area after August 5 — or in years prior.

When shown the Indian news reports attributing to Kaincho Bala claims that their home had been attacked and family members raped or killed, Nitai Roy looked stunned.

“I don’t understand why Grandmother would say such things,” he said. “Maybe she was frightened after being caught by the BSF at the border and said it out of fear.”

He added: “This neighborhood is new. We built our house here only three years ago, after moving from another part of Shukdebpur. For the past three years, Hindus and Muslims have lived together peacefully. Everyone is busy with their own work. A local organization is even building a temple here for us. We’ve never had any trouble here.”

Community Leaders Dismiss the Claims

Local leaders echoed the family’s testimony.

Khokon Chandra Roy, Bala’s nephew and secretary of the local Puja organizer, said: “She went voluntarily to visit her daughter in India. No one forced her. What she said after being caught is fabricated. No attacks happened here.”

Khaled Mahmud Sujon, a UP member and former classmate of Manik Chandra Roy, said: “She lived with her two sons’ families. One son disappeared when we were young. Two daughters died long ago. Our Ward has more Hindus than Muslims. No communal violence occurred before or after August 5.”

Parbatipur’s union chairman, Nazrul Islam Sarker, was categorical: “If such horrific incidents had occurred, I would know. If so many family members were victimized, the whole country would know. These reports are entirely baseless.”

What Minority Rights organization says?

The Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council (BHBCUC), Bangladesh’s most prominent minority rights organization, publishes annual reports on communal violence. Its documentation is so exhaustive that it was sometimes accused of exaggeration.

The group issued two reports covering the period after Hasina’s fall — one tallying 2,010 incidents from August 4–20, another listing 174 incidents from August 21–December 31.

Both reports (can be seen here) contain detailed district-level accounts. Neither mentions any attack in Parbatipur, Dinajpur, let alone rape, murder, or abduction in Paschim Shukdebpur.

Contacted in July 2025, the Council’s organizing secretary, Advocate Dipankar Ghosh, said:

“All incidents we were aware of between August 5 and December 31, 2024, were included in our reports. We have no record of rape, murder, or disappearance in Parbatipur.”